For the past six months, the Guardian’s editorial tools team has been building a product for the organisation to manage its digital content through the production process. Called Workflow (yes, it’s unimaginative), the tool tracks content from inception through to publication. We’re not going to explore the tool itself. Instead, we’re going to look at the way we built the product, as I believe there is a lot to show about the way the team has worked together. The team was comprised of three developers, a UX architect, a UI designer, a QA, an agile project manager, and a product manager, all with a broad range of experience building software.

The workshop

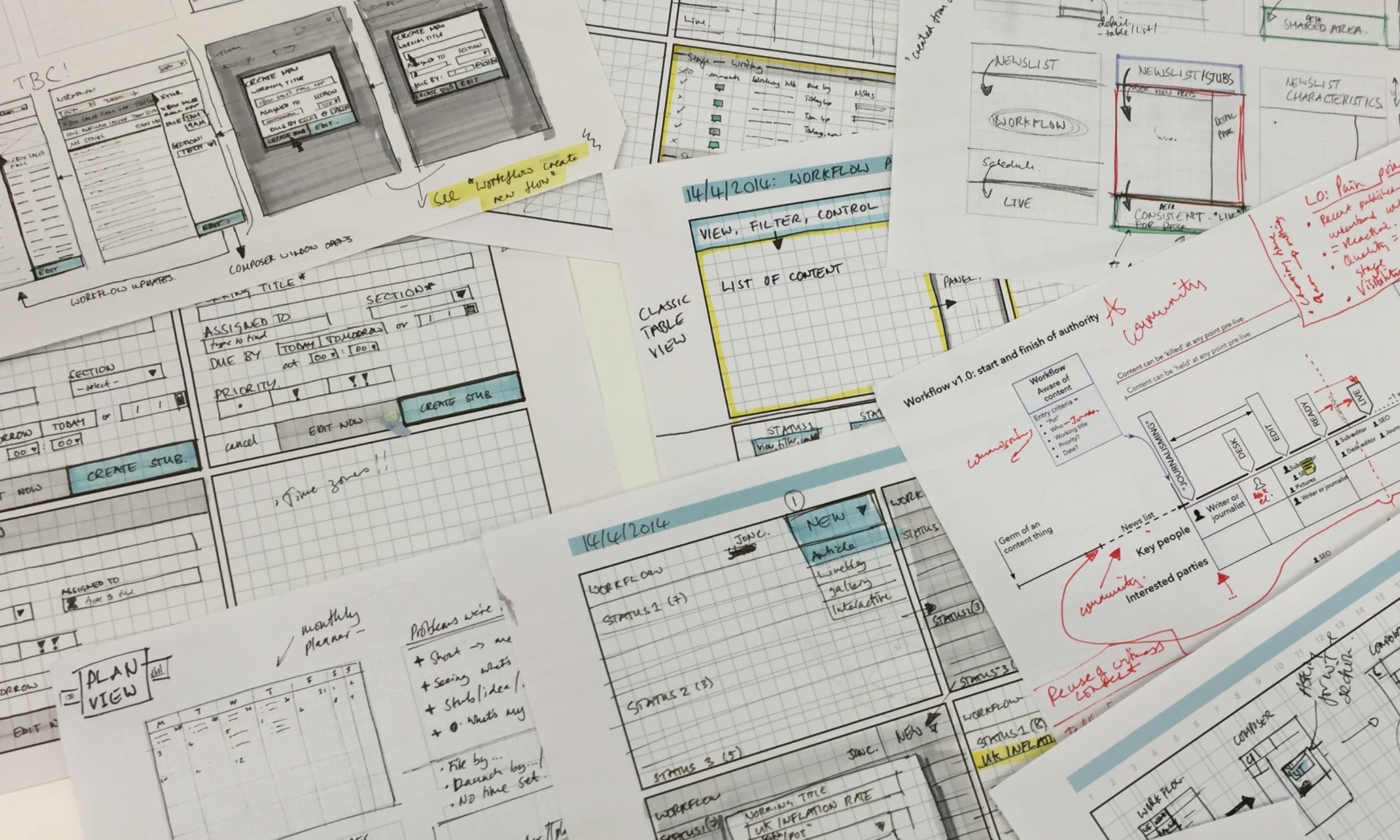

Before the team had even come together, we held a workshop in the Guardian’s UX studio to understand the scope of the problem. The workshop was structured so that everyone had an opportunity to contribute. The attendee list was deliberately chosen to maximise the range of opinions and depth of experience, from both an editorial and development perspective. It passed the ‘sensible people test’: remember, we were trying to understand the problem, not necessarily the weight or validity of each opinion at this stage. The range of user stories that were generated was staggering in both volume and range of thinking.

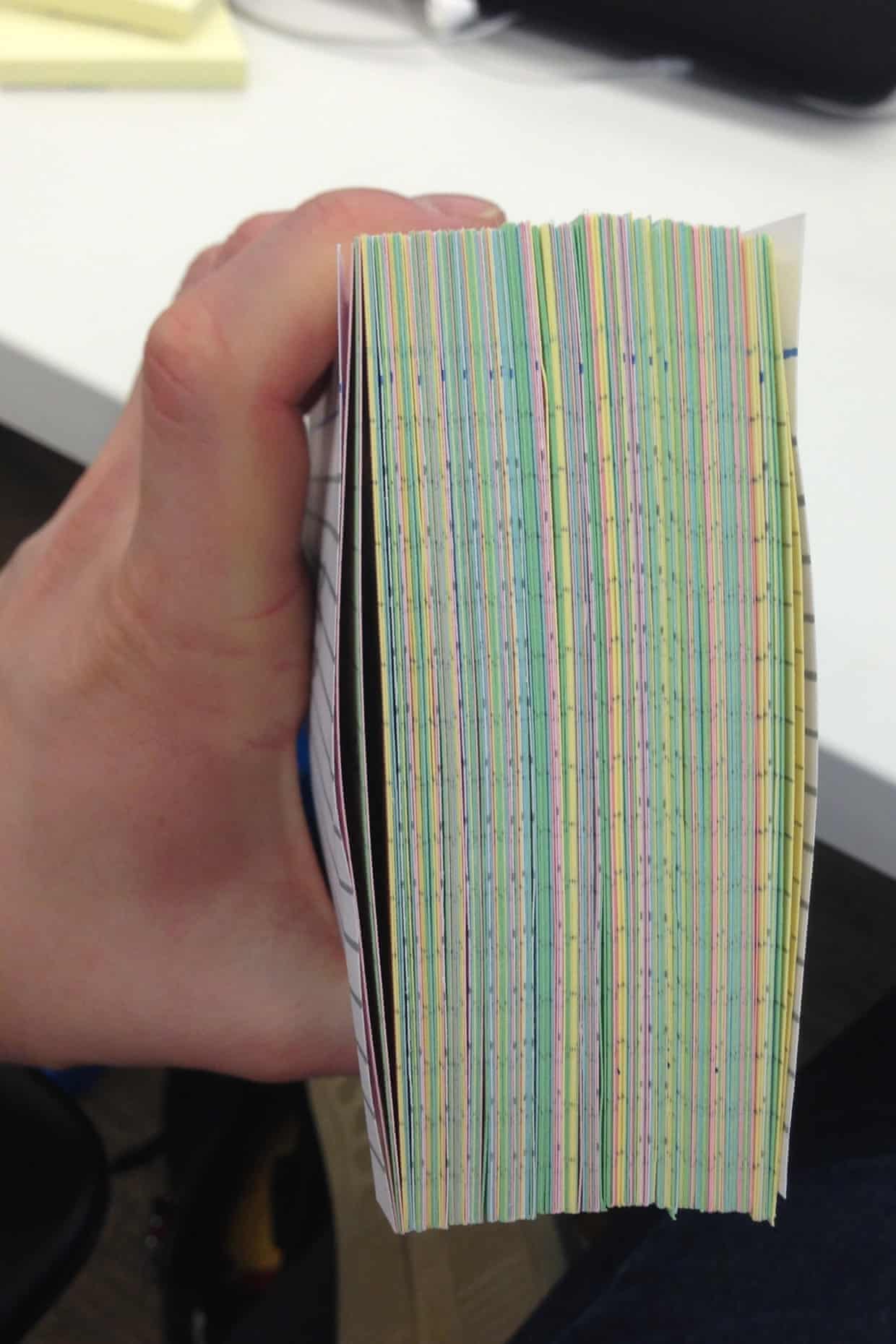

We’d generated over 150 user stories , many of which were epics, and so would naturally break down into more granular stories. Some examples:

-

As a sub-editor I want to see all the stories in the department I am working in that have not yet been subbed so that I can sub them

-

As an editor I want to see content within my desk, what stage it is at and who is working in it so that I can ensure we will meet our deadlines

-

As a fronts editor I want to see all content that is being prepared for publication so that I can plan what will go on my front and when

This volume of stories covered all aspects of the publication process, from story planning, through to post-publication promotion. David Blishen—our group product manager—slimmed down the cards into a core set of ‘stuff’ which represented our minimum usable product.

Bring the anarchy

The first meeting as a team was to decide on the way were were going to structure the way we work. Agile was the obvious choice, right? Think on. Our lead developer Stephen Wells pitched a number of methodologies to us, and the one that stood out was ‘developer anarchy’. Broadly speaking, developer anarchy works on a belief that if you let a sensible development team understand the business problem—in our case, managing content through a production process—then you’ll end up with a quality product. We’d all worked in teams where a sense of problem ownership was low and we wanted to see what would happen if we took a bit more control. Thus: the team became anarchistic in its approach.

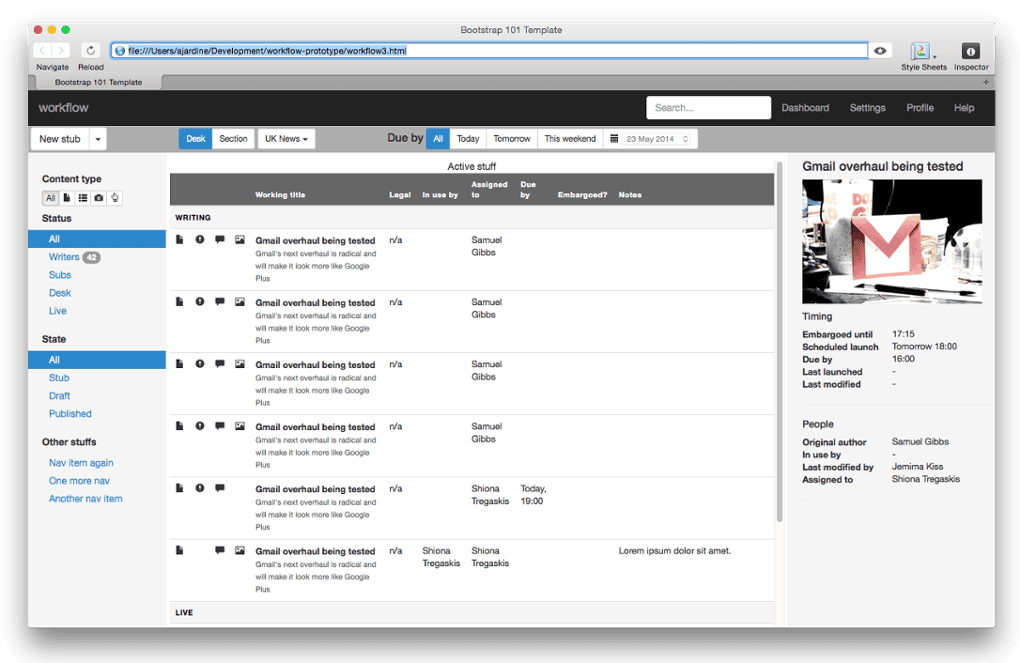

We decided pretty early on that we would forgo traditional rounds of flat designs, and build a prototype product that we could test with our editorial users. I took the time to build a clickable HTML/CSS/JavaScript prototype, which allowed us to quickly get something on screen that felt real and proportional.

Much to my surprise (and to be fair, theirs once they looked at my code!) the developers on the team took this work, and hooked up a back end. The working prototype was rough, but it did one thing: track a piece of content from inception to publication.

The goal of this working prototype was to test concepts and execution to learn about what worked as a team. We learned really quickly (our editorial colleagues aren’t a shy bunch) where functionality was lacking, and what we’d missed. Our decision to test ideas and concepts meant we were testing questions and hypotheses against the product, and capturing that learning so we could iterate and refine. Some concepts were thrown out, or just didn’t work as expected. But as a group, how did we most effectively learn and understand the problem at hand?

Everyone on the same page

One of the main challenges I’ve seen in my time doing UX is “moderated access” to users. It’s my belief that all members of the team should know the users, be able to speak to them, collate problems and understand the problem space in which they are operating. As UX people (and product people are also guilty of this), it’s tempting to be that bridge between users and the development team. You know how it goes: have a conversation with a user, understand the problem, hive oneself off, then pitch a solution back to the team. But there’s a real issue with this. By not having a developer in the conversation, you end up being the arbiter of all knowledge, and contribute to the marginalisation of understanding. You quickly arrive at a situation where the whole team doesn’t see the full extent of the problem, and so the technical solutions are always going to be predicated on a subset of knowledge. The other consequence is that the team don’t have a full sense of ownership, and so motivation can often suffer. We worked really hard in the Workflow team to have a developer at every conversation and session where we were speaking with users. Similarly with training, we always had a developer there, or indeed, no UX person at all.

Stand ups Sit downs

It’s fair to say that during the early phases of the product when the team was in the “build, test, learn” phase, our daily stand-ups were actually spent sat down talking about what we’d all learned the previous day, and what we might want to do about it. The daily sit downs were effective. Everyone knew everything that was going on. Developers having a sense of ownership of the problem was powerful – they would pick up a piece of work that was both important and would solve a problem we’d identified as a team, irrespective of whether it was user-facing or not. We also did away with sprints, not least because it was obvious to everyone on the team what the next thing to be tackled should be.

But what are the implications from a user experience perspective?

By getting everyone onto the same page, it made my job an order of magnitude easier

It’s been a product-creation epiphany. By getting everyone onto the same page, it made my job an order of magnitude easier. Why? There was almost certainly a developer present when a problem or opportunity is spotted. I’ve spent too much of my time pitching legitimate problems (and solutions) back to development teams in the past, attempting to get “buy in” for problem (or solution). By having everyone on the team be part of the earlier stages in that process—the problem identification bit—the end result has been excellent. The what, when, why is just obvious (even if the solution isn’t).

It’s important to remember this works particularly well when you’re working in the same building as your users. When they’re not in the same building, it can be a challenge. I wouldn’t suggest this is easy when they’re not co-located, but the same principle applies: in any research, get the whole team involved in the process, and get them to know your users without the lens of a UX person filtering out.

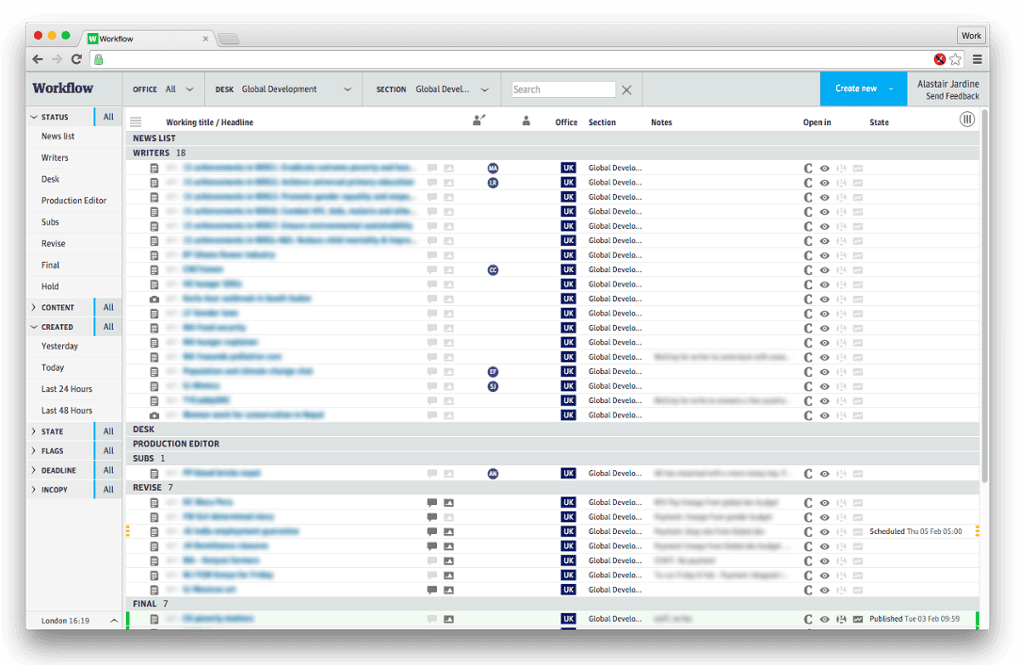

Where did we end up? Here’s a screenshot of the current product, which is being happily used by our editorial colleagues:

Lessons learned

The biggest lesson learned is that giving people the ability to work on a product in a way that they see fit is a liberating and ultimately rewarding way to develop a product. It absolutely requires the team to understand the problems that are being solved. By empowering the team to speak to people directly, you end up with a greater corpus of understanding, which leads to better decision making. You might disagree about the solution, but you know that the problem is shared.

And as a UX person? We need to champion whole team understanding and user engagement, and not get in the way. If you’re doing research and playing it back to the team at a later date using a presentation, you’ve probably just disconnected from the team. If you work in the same building as your users and team for eight hours a day, then the ‘playback’ is the ongoing conversation with users and the team. You might need to formalise things occasionally, but it should be as a last resort.

One excellent example of team ‘connectedness to the problem’ is features requests: it’s been rare that we’ve not discussed or suggested features in advance of our users actually requesting them.

A final thought. To make this work, it does require an engaged development team with a certain level of maturity and confidence, so bear that in mind. It won’t work for all teams, but where it can, embrace it.