At The Guardian, like many engineering teams, we rely heavily on CI/CD pipelines to keep our software fresh, secure, and reliable for our users. Our workflows hinge on GitHub Actions, so when things go wrong or get expensive, the impacts are felt quickly. This is the story of why we moved away from GitHub-hosted runners to using our own self-hosted runners, what the process involved, and what we’ve learned along the way.

What Did We Do Before?

For a long time, all our automation ran on GitHub-hosted runners. The set-up was minimal: we simply needed to configure our workflow files to run on the runners of our choice (mostly macOS runners, since we work on an iOS app, but where possible we used Linux runners to keep costs down) and then we could let GitHub orchestrate the infrastructure. The only real maintenance involved was keeping an eye out for new macOS versions as Apple released them, and then updating the relevant configuration. Sometimes, GitHub took a little longer to roll out those updates than we would have liked, but overall, things ran pretty smoothly.

Why Did We Move?

Despite the generally low maintenance cost, there were a few pain points with GitHub-hosted runners, which encouraged us to look for alternatives:

- Pricing: Since we’re building an iOS app, most of our actions need to run on macOS. GitHub Actions running on macOS have a minute multiplier of 10 in comparison with actions running on Linux. Our monthly bills were considerably higher than those of other teams in the department, and we wanted to explore whether there were ways we could reduce this. Larger runners, while more powerful, came with an even steeper price tag.

- Timeouts and Speed: Builds sometimes ran frustratingly slowly, leading to unnecessary timeouts and delays. When a build timed out, we’d need to start the run again, causing the costs to rack up even more.

- Unpredictable Upstream Changes: Occasionally, GitHub would roll out a new runner image which caused extreme slowdowns in build times. These updates were outside our control, and we just had to wait for the GitHub Actions team to roll them back or fix them. We actively monitored and contributed to public issues in the GitHub Actions repository, such as https://github.com/actions/runner-images/issues/11509, in an effort to apply some pressure in this regard.

We’d had some success using Xcode Cloud for a while in 2023/2024, but when it stopped working out of the blue for us in March 2024 we had to restore our GitHub Actions workflows in order to unblock our releases.

Other options could have included third-party mobile CI solutions such as Runway and Bitrise, but we wanted to explore our in-house opportunities first.

Finally, we experimented with cutting our costs on GitHub-hosted runners as much as we could, trying to speed up our builds by making changes such as skipping unit tests on draft PRs, optimising our use of the GitHub cache for our Swift packages, and moving to larger runners to see if the cost-saving from the increased speeds outweighed the higher per-minute cost, but none of these solutions made a sufficient difference to our monthly bills.

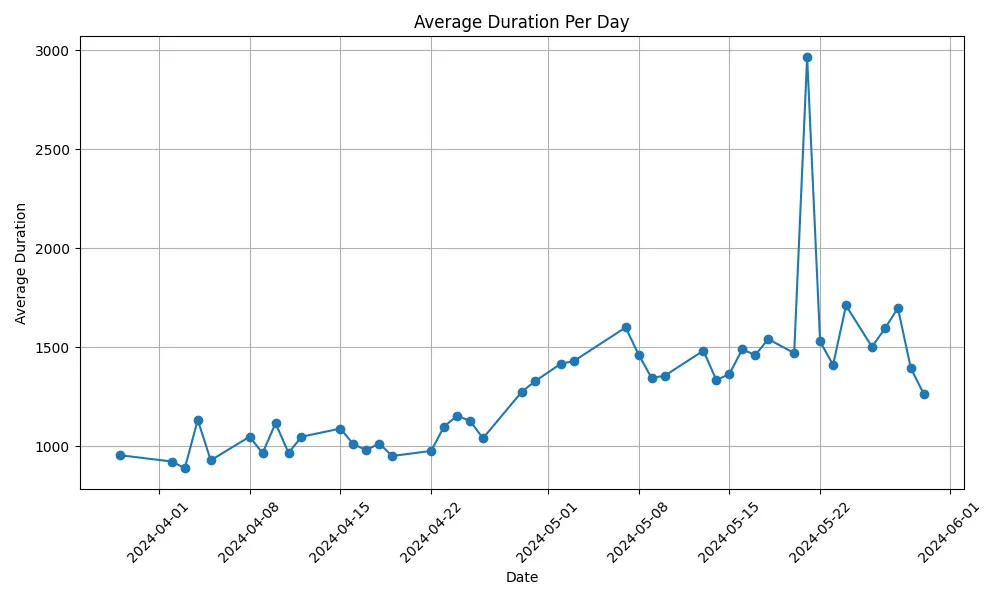

As part of the above experiments we also did some work on visualising our build times. The graph below dates from the start of the experimentation process, so it doesn’t capture any of the improvements we did manage to make. However, it provides a revealing insight into how exposed we were to issues outside our control - the huge spike in May was caused by a GitHub outage that we just had to wait for them to resolve.

The daily duration of running unit tests on GitHub-hosted runners. Illustration: Simone Smith

Why Self-Hosting?

We had an unused Mac Mini in the office, which significantly lowered the barrier for experimenting with a self-hosted runner. We decided to attempt running our GitHub actions locally and see whether this would be a better solution for us.

Setting It Up

The initial setup involved following GitHub’s official self-hosted runner instructions. In brief, this involved installing the runner software, authenticating it against our repo, and updating our workflows to run on our Mac Mini rather than GitHub-hosted machines. We also needed to set up remote access for developers on our team to manage the machine, so that even though it’s a self-hosted machine, we don’t have to actually be physically present to use it.

In reality, the experience was a bit more trial-and-error than plug-and-play. Transitions like configuring DerivedData folders for Xcode builds and cleaning up artifacts between jobs required extra care. Since our local runners aren’t ephemeral (unlike cloud instances), we had to devise strategies for keeping the workflow runs clean - deterministic DerivedData folder names for each run, post-job cleanup steps, regular deletion of old Xcode versions and simulators on the machine, and ensuring that the keychain was deleted after failed deployment-related actions, to prevent future failures.

How’s It Going?

The Positives

-

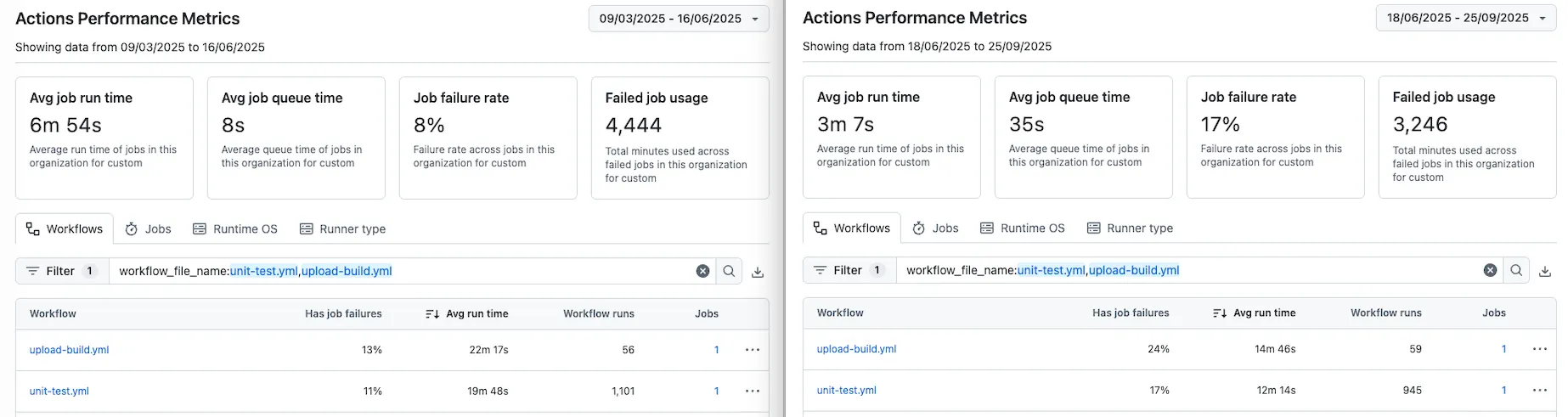

Speed: The difference was immediate. Builds ran much faster and stopped timing out, as well as becoming more stable and predictable. Build times are now under our control - and if they slow down or become problematic, we now have the freedom and ability to take steps to improve them ourselves. The images below show the data for two of our slowest workflows (running unit tests and uploading builds to App Store Connect), in the 99 days before and after migrating to self-hosted runners. We can see that:

- unit tests run 50% faster

- uploading builds is 60% faster

- the average run time across all workflows (represented by the ‘Avg job run time’ box at the top) is now over 120% faster

The failure rate has increased slightly, but this is partially explained by the initial teething troubles we experienced at the start. Furthermore, now that we’re no longer paying for each minute we use, we don’t feel the pain of job failures in the same way.

The average duration of running unit tests and uploading builds on GitHub-hosted runners compared to self-hosted runners. Illustration: Simone Smith

- Debugging: Being able to log directly into the machine, check logs, and debug issues was a real luxury compared to the black box of GitHub-hosted machines.

- OS Upgrade Control: We can update to the latest version of macOS whenever we want, and are no longer at the mercy of upstream broken runner image updates.

- Cost: Our monthly bill dropped by roughly £400.

The Negatives

- Concurrency: We currently have four concurrent runners configured on the machine, so jobs sometimes end up in a queue before they can be picked up. But with the improvements in speed, these queues are short, infrequent and rarely problematic.

- Maintenance Overhead: More control means more responsibility. The Mac Mini needs attention: cleaning up after Xcode upgrades, clearing out old simulators, ensuring there’s enough free disk space, and keeping the runners tidy.

- Teething Problems: The shift to non-ephemeral runners meant, at first, old job data could stick around. If jobs failed, DerivedData folders lingered, keychain entries weren’t deleted, and we experienced failures that we needed to fix ourselves via cleanup steps.

- Reliability: Maintaining physical hardware means physically rebooting if it crashes, and we need to ensure that it has a consistent power supply. Our server room is well equipped for this, but it’s something that needs to be taken into account.

Learnings for the Future

- Bigger Is Better: It’s easier to manage a single, more powerful machine running multiple runners than it would be to juggle a fleet of smaller machines each with one runner. Maintenance and upgrades happen just once, not repeatedly.

- Always-On Reliability: A continuous power supply (plus remote access for management and restarts) is essential in order to prevent interruption to builds.

- Consider a Cleanup Strategy: Plan for proper cleanup routines - think ahead for artifact management and disk space monitoring.

Switching to self-hosted runners wasn’t frictionless, but the speed, cost, and control gains justify the effort. If you’re wrestling with sluggish pipeline builds or unpredictable updates, it’s a path worth exploring, just be prepared for a bit more hands-on maintenance than is required with GitHub-hosted runners.