Leaving Scribe

Just over five years since Scribe was born we have decided to bring to an end the active development of the project. We are working on implementing a new text editor based on ProseMirror that we hope to open source in the future.

For those of you who continue to use Scribe you probably will have noted a lack of active development recently. In fact, our last minor version (v3.3) was in March 2017 and our last major was a year before that. All things considered it seems right to detail our plans for the future. But in order to explain what we’re replacing Scribe with, it’s probably worth a short catch-up on why we created Scribe in the first place and why it doesn’t fit our current requirements.

Why did we create Scribe?

Scribe is a text editing engine that was built to abstract away the idiosyncrasies of text editing in the browser and to expose a means of extension through plugins. Back in 2013, as it became clear we were outgrowing our TinyMCE editor, we decided to look for a more powerful alternative that would help us push our editor further. At the time, each of the alternatives had a subset of the things we wanted – such as fine-grained copy/paste handling, multiple instances per page, and custom menu bars – but none of them had everything we needed. Consequently, the decision was made to build a full-featured text editor at the Guardian: an editor that could flex to our changing editorial requirements; that was able to cope with text editing at newsroom pace; and that allowed us to implement features that our editors were used to from other native applications such as InCopy.

Scribe delivered on all of those things and powered (and continues to power) parts of the content management system that the majority of our editors use. However, as new apps and text editors have come out, features the likes of which we perhaps had not considered at the outset have become commonplace – such as the collaborative editing and inline annotations found in Google Docs. Additionally, some of Scribe’s plugins suffered from long-standing, fiddly bugs that proved difficult to fix due to browser inconsistencies and issues around Scribe’s underlying model.

The problems with Scribe

Scribe is essentially a wrapper around contenteditable and execCommand, the main two primitives for creating text editors in the browser. Its main aims were to smooth over the inherent issues that came with these things, to handle the browser bugs between the implementations of contenteditable, and to normalise the inconsistencies that arose from using HTML as a model. contenteditable has oddities and behaviours that are infamous among those that have tried to implement an in-browser text editor and, while there is an open draft to fix many of these things, the current state (which is, in fact, the same as the state in 2013) means that a vanilla implementation of these things is almost certainly not sufficient for even the simplest of text editors – especially if you care about semantic markup. There are many good articles focused on the problems, benefits and future of contenteditable, but it’s worth laying out a quick summary of the issue that caused us the most problems when building and maintaining Scribe: the use of HTML as the data model.

HTML as a model

HTML is a great way to mark up and render rich text, but when it is also used as the data model for rich text, it falls down in a few key areas. A good example of this is that one semantic piece of text has many different representations in HTML. Take for example the following text:

Scribe

Below are only a few representations of this in HTML:

<em><strong>Scribe</strong></em>

<strong><em>Scribe</em></strong>

<em><strong>Scr<strong></strong>ibe</strong></em>

<em><strong>Scr<strong></em></strong><em>ibe</em></strong>

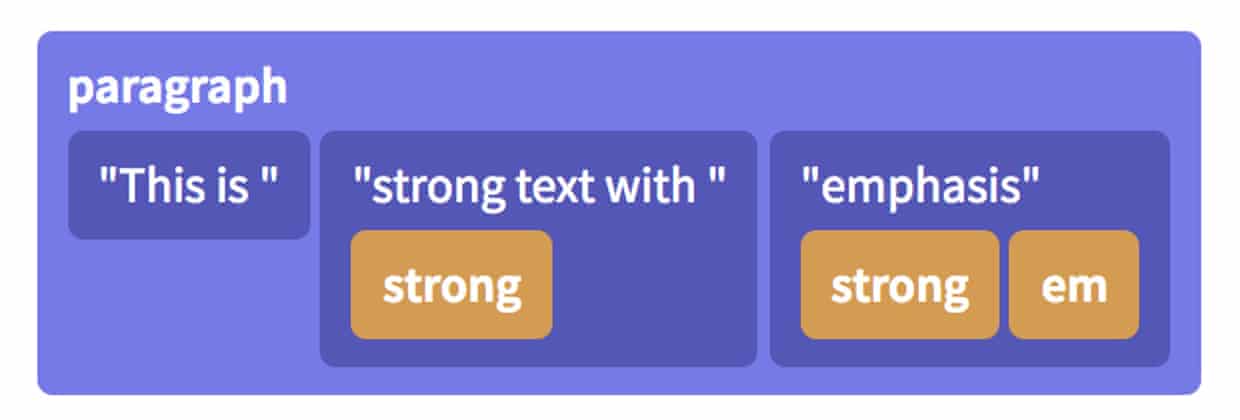

All of the above are valid representations in HTML, and you can encounter any of these different representations when using contenteditable (aside from the fact that contenteditable uses non-semantic b and i tags instead of strong and em) and it’s perhaps not totally clear which the “right” one is. There are, of course, ways to normalise these variants to a single canonical representation (and Scribe does this very well) but the DOM API is not made in a way that facilitates this, so when managing complex markup, or inserted content – either through pastes or collaborative edits (mandatory aside: HTML as the model isn’t the only difficulty with collaborative edits by any means) – managing these issues through the DOM API becomes cumbersome and prone to error.

Another area where HTML as a model falls down is editor-only annotations (markup that helps the writer but is detrimental to the reader). Take for example the need to highlight a word in the text that meets some criteria (a suggested tag, or some legal issue around using this word). You may want to show an inline annotation to ask the editor whether they want to add this as a tag. A possible representation of this in HTML in the editor is:

<p>

Scribe uses

<mark>

<div data-annotation="1" contenteditable="false">

<p>Add this as a tag?</p>

<p>

<button data-accept>Yes</button>

<button data-reject>No</button>

</p>

</div>

contenteditable

</mark>

</p>The problem here is that now we have data that is not part of the document, and yet is modelled as part of our document. This is technically solvable but again, the DOM API is not well suited for handling this sort of data modelling, especially when the usage of these features becomes more complex. As you start to force more complex features through an HTML data model, you have to do more and more work to get around HTML’s limitations around modelling a rich text document, and you hit more and more of the browser inconsistencies. Managing all of these issues together, we found that innovating with Scribe became slow and difficult and was more about battling bugs than implementing features, and ultimately development slowed to a crawl.

The Guardian after Scribe

This brings us to the present day. As mentioned above we are moving to ProseMirror, an open source tool for building text editors that is under active development and has users including the New York Times. At the time of writing our main body copy editor is being driven using ProseMirror.

Perhaps the first thing to note is that ProseMirror still uses contenteditable under the hood. Despite the problems with contenteditable you get a lot of things out of the box with it that are currently almost impossible to implement without it: platform-native keyboard shortcuts, support for IMEs, right-to-left text editing etc. In fact there is a section in the W3C spec about the HTML 2D canvas that explains why not to implement a text editor on the canvas – plenty of which can equally be applied to describing why not to implement a text editor outside of contenteditable. Like Scribe, ProseMirror abstracts away contenteditable and allows granular extensions through plugins.

The important difference between Scribe and ProseMirror is that ProseMirror implements its own model layer that has a one-to-one mapping from semantics to the model, and an API that is made with document transformation in mind – not least collaborative editing.

In ProseMirror, inline content is flat rather than a tree, which means operations such as changing styles on text don’t require any tree manipulation. And while nodes (h1, p, blockquote etc.) are still modelled as a tree, this accurately models how users think about things such as paragraphs and lists, and it’s almost always how they’re rendered when a reader consumes an article.

Aside from the much more sensible model and many other niceties, ProseMirror also handles the browser bugs/inconsistencies in one place, which allows us to get back to writing code that is closer to our domain problems than before.

We hope in time to be able to get our editor to a point that it can be open-sourced, but we’ll only do this if we believe we have the documentation and resource in place for that to be useful to users outside the Guardian.

The future for Scribe

Currently we are still using Scribe in many places inside the Guardian. The number of these instances will go down as we continue to work on our new editor but we may continue to make small security fixes, if and when required, throughout this period. It’s unlikely that we will be able to transition the canonical Scribe repository to maintainers outside the Guardian, especially as we continue to use it, but given that the project is open source and under an Apache license, we hope that forking will fulfil all the requirements of anyone looking to continue using Scribe outside the Guardian.